It concerned Stephen Hawking’s sceptical reaction to Higgs’s work and was duly printed on the front pages of newspapers to imply that Higgs had made a “deeply personal attack” on a genius who used a wheelchair, leading to unnecessary tension between the two physicists. An offhand remark by Higgs, while out to dinner on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, was picked up by a journalist. But Close justifies Higgs’s name being attached to the particle, because he both predicted that the boson exists, and suggested a means to identify it.Ĭertain details are fascinating. He cites others who claim that, because of all the developments leading up to this insight, Higgs was actually “a rather minor player”, or that his role was a matter of luck. Close deals well with the tricky and potentially controversial issue of the five other theoretical physicists who independently came up with the same concept around the same time. The breakthrough idea was that a type of particle called a boson could eliminate the problem that stymied attempts to account for mass. But a key element was missing - a way to explain how fundamental particles can have mass, and why they have the masses that they do.

#PETER HIGGS PLUS#

These influences fostered his interest in quantum field theory, which ultimately forced him to confront the most challenging puzzle that the discipline then faced: why is there mass?Įlusive parallels Higgs’s personal story with a sketch of the numerous pieces that went into the architecture of the standard model: the theoretical framework provided by quantum field theory, the solutions to numerous problems in the model’s structure, plus all the particles and fields that the theory encompassed. We learn about factors that shaped Higgs’s career - his early education in Bristol, UK, and degree at King’s College London, inspirational figures (physicists Charles Coulson and Paul Dirac) and the role of political activities, such as his membership of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, in forging a network of contacts. Close’s attention to Higgs the person distinguishes this book from science writer Jim Baggott’s 2012 book Higgs, which is more about the science and spares only a few pages for the man himself.Ĭlose gives a quick account of Higgs’s mentors, interests and the episode of depression that sidelined him from physics. The Higgs was triumphantly discovered at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) near Geneva, Switzerland, in 2012. In 1964, Higgs contributed a crucial piece to that model, theorizing the existence of a particle - later known as the Higgs boson - that imbues all other particles with mass. Elusive - a title that alludes to both the man and the subatomic particle that he predicted - ended up as a breezy yet informative book that entwines the story of Higgs’s life with that of the construction of the grand theoretical edifice known as the standard model of elementary particle physics. On top of all that, physicist Frank Close took on the task of profiling him during the COVID-19 pandemic, which wrecked Close’s plans to dig into archives and consult Higgs extensively.īut the author is, one can’t resist saying, a Close friend of Higgs, and conversed frequently with his subject by landline. A 93-year-old British theoretical physicist who won half of a Nobel prize in 2013, he is notoriously shy, inaccessible by e-mail and mobile phone, self-deprecating and averse to the spotlight. Peter Higgs is not the easiest subject for a biographer to tackle.

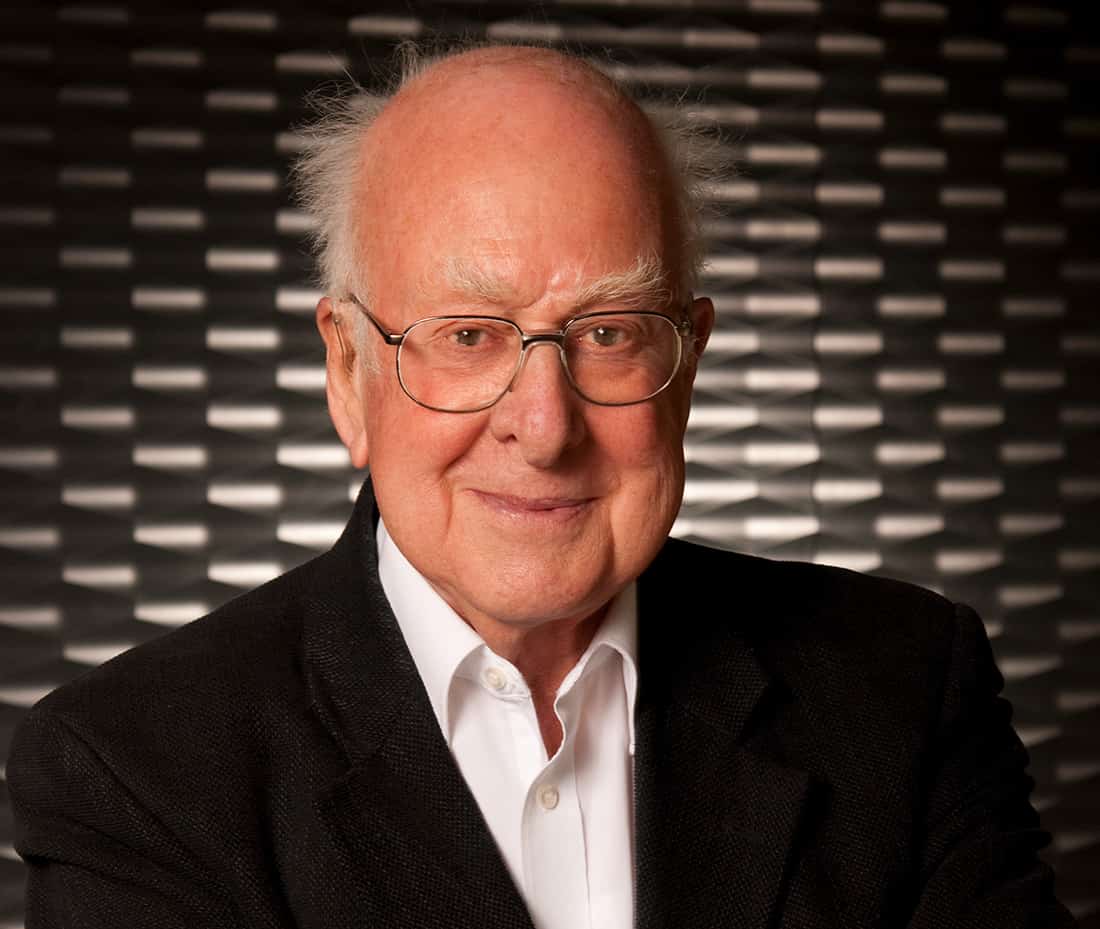

Credit: Peter Macdiarmid/GettyĮlusive: How Peter Higgs Solved the Mystery of Mass Frank Close Basic (2022).

Peter Higgs predicted a boson that completed the standard model of particle physics.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)